Reason to Believe – Aimee Mann and Michael Penn

“It’s too utopian. It’s a policy of rainbows and unicorns. It’s not enough to just have faith; you need a way to get things done.” These accusations will sound familiar to the supporters of Bernie Sanders. They’ve been leveled with regularity over the campaign. Some might say with monotony.

And each time, the Sanders supporters have responded with a straightforward query: that his ideas sound impossible is precisely the problem. After all, what’s actually preventing us from ensuring that every American gets basic health care, a chance at a good job capable of putting food on their table and a roof over their head? Why can’t the richest country in the history of the world provide free college for anyone who wants it? These aren’t technical or material problems, but simply down to a lack of political will. And if that’s the case, isn’t that fact itself a searing indictment of our current political order? What further reason do you need to support change?

However, for those less inclined toward the Sanders revolution, this rhetorical move is exceptionally aggravating, to the extent that it willfully conflates means and ends. To them, it’s a naïve move grounded in the faith that pure intentions are sufficient, that ultimately heroes will triumph and villains receive their just deserts. But for these folks, often self-styled as ‘realists,’ the right beliefs aren’t enough. The world is a harsh and complex place, filled with intractable problems that can’t be resolved by broad strokes. And out here in the real world “women never really faint, and villains always blink their eyes.”

The politics of faith vs. the politics of realism

So here we have a spectrum: those who have faith vs. those who insist on being ‘realistic.’ Obviously, many people will see elements of both in themselves. But this simple difference in attitude explains quite a bit of the vitriol that characterizes this debate. Passions run high here not just because people disagree about policy questions or ideological goals, but because the entire frame of the conversation is structured by these underlying attitudes.

This is why some of the most antagonistic conversations revolve around questions that are ostensibly neutral. For example: ‘who is going to win the nomination’ is an empirical question, not a normative one. Even if Sanders is the ‘best’ candidate, that tells us nothing about whether he’ll accumulate enough delegates (except insofar as his ‘superior’ candidacy can be expected to win him votes). So why does it inspire such vituperative dispute?

The simple answer is: people don’t like bad news, and will do anything they can to avoid acknowledging it. Conversely, people don’t like stubbornness, and will do anything they can to punish it. But I think it’s actually more complicated than that. We don’t need to assume the worst of people to explain these fights. Because ultimately what’s going on here is much deeper than just accuracy in prediction.

What faith tells us about ‘facts’

At a fundamental level, this is an epistemological problem. At stake is the filter through which we encounter ‘facts.’ For those who believe, Sanders doesn’t look like a longshot, because that claim presumes the inevitability of knowledge-frameworks, which they see the entire Sanders campaign challenging. And they find succor for this faith, because, well, haven’t the pundits missed on all kinds of assertions already?

On the other side of the conversation, indeterminacy is sharply distinguished from meaningless. For the realists, the limits of punditry over the past 12 months obviously inspire some reassessment. But to treat this as the death of prediction risks throwing a whole bunch of babies out with the bathwater. After all, this is how science works. You start with what you (think you) know, and evaluate new information. Evidence of past errors inspires self-reflection, reassessment of models, and so forth. Not a retreat into the irrefutability of faith.

And there’s something to this. After all, we can see all too clearly what happens when ‘what we want to be true’ is permitted to intrude into ‘what actually is true.’ Global warming denialists, anti-vaxxers, anti-evolutionists, those who shut down medical research or research into gun violence or any other issue simply because they don’t want facts to intrude on their desires. I’ve read my Thomas Kuhn, of course, and I’m all too familiar with the biases and prejudices built into all scientific arguments, but that doesn’t disprove that some degree of objective analysis is the lifeblood of progressivism. When we allow faith to replace reason, we ourselves no favors.

And with all that, you can look at the facts as they now stand. You find:

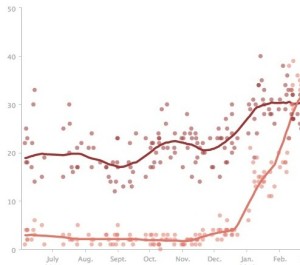

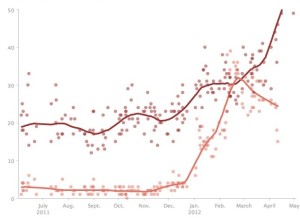

- Sanders still faces a huge gap in delegates

- For all the fluctuations on the calendar, the underlying demographics have held pretty stable throughout the race.

- For all that Michigan was a huge polling failure, on the whole the polls have been reasonably accurate

- Sanders has done very well in caucuses, less well in primaries

- Sanders has done well in open primaries, less well in closed primaries

And then you look at the remaining contests and see: they are almost exclusively primaries, many closed primaries, in states that are on the whole far more racially diverse than those Sanders has been winning, and in which Sanders is tends to trail in the polls by significant margins.

Taking in all this information, it is quite clear to me that it would take a massive change—well beyond even the ones we’ve already seen—to erase this deficit. That’s just a reality, not a value judgment.

But, of course, many people disagree with that assessment. They will say ‘those are assertions, not facts.’ And that’s the rub of things, isn’t it? Because what’s really going on here is a dispute not just about which facts truly hold, but more importantly about how such debates inflect the sort of world that we believe in.

And that realization needs to be a bigger part of these conversations, because it helps us all understand what we’re talking about when we talk about predictions. And it helps remind us of the limits of argument here.

The role of atheists in conversations about faith

To clarify things, let me propose an analogy. I think that, at a certain level, the debate over the facts of the race (Sanders can’t win, #feelthemath, etc.) scans quite a bit like the Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens going after religious people. They may or may not be ‘right,’ but they are definitely jerks.

So I have a lot of sympathy for people who see the positive side of things, who believe in the potential for a big change. And I empathize with the frustration it must cause to constantly encounter aggressive demands to ‘look at the facts!’ Because in some sense, it just kind of misses the point.

That said, I think that characterizing this as partly a conversation about what to believe also helps illustrate dangers in the other direction. Here I’m thinking about the accusations that fly from the Sanders supporters, which characterize all descriptive efforts as nothing but ideological shade. Which portray ‘the media’ as a stalking horse for the Clinton campaign, who is actively trying to help her win by painting a narrative of inevitability.

I see these arguments as, in an important sense, mirror images of the attacks from the other side. They are seriously overdetermined, and grounded in assumptions that are thoroughly ungenerous

Now, I don’t mean to suggest that there is no valid space for critiques of this sort. It is certainly true that media frames inject bias into political coverage, just as it is true that derisive attitudes toward leftist claims (seen as sophomoric, utopian, infeasible) informs the way general society understands those issues. The superdelegate system raises legitimate concerns. It’s not clear that the Party ought be in charge of scheduling debates. And so forth. These are real problems, and one of the wonderful things about the Sanders campaign has been the broader mobilization that has emerged around it, which has sought to break the stranglehold of those old characterizations.

The point is just: arguments of this sort run a real risk becoming so firmly grounded within one faith community that they utterly deny the possibility that others might also be acting in good faith to truly held beliefs of their own. Many reporters, for example, are well-aware that all reporting carries tinges of ideology. But they believe (truly and wholeheartedly) that to strive for descriptive clarity is a good in itself. They are neither the willing shock troops of ‘the establishment,’ nor are they unwitting stooges. They are well-meaning people doing work with real value.

Does that excuse them of all social responsibility? Certainly not. Just as those who made the bomb cannot claim moral purity simply because they were conducting ‘pure science.’ But I worry that this aspect of responsibility risks overriding everything else. That those who seek descriptive meaning are all painted with the same brush.

Understanding the faithless

So this invites a question: for those who live in faith, how will they regard those who reject the good word? Will they regard them skeptically? Will they see the refusal to accept the truth in their hearts as evidence of deep-lying sin? I see two risky possibilities. They might be categorized either as infidels (non-believers who must be shunned, or even destroyed) or as apostates (corrupters of the true faith). Broadly speaking, conservatives might be understood as the former, liberal as the latter.

Such responses worry me, for all the reasons that I worry about the problems of secular politics in a world defined by faith. Because the fact is: we don’t all share the same faith. The things that animate us are not identical, nor should they be. And I worry about political movements which refuse to accept this underlying reality. Which presume that there is only one true faith, and which therefore regard antagonism to its precepts as in some sense forsaken.

You see that kind of thing on display in assertions that the ‘system is rigged,’ which deny agency to the millions of living, breathing humans who show up to polls to cast ballots for other candidates. You see it in criticism which regards media efforts at neutrality and objectivity as evidence of crass opportunism or crony politics. You see it in all the arguments stacked together, which assert that Sanders would have won, if not for the efforts to rob the people of their chance. And so forth.

These ‘stab in the back’ narratives are potentially extremely corrosive, because they regard all obstacles to the ushering in of truth as illegitimate on face. And they tend to fixate on relatively insignificant issues, rather than addressing the larger reality of a world in which people simply do not the same truths. ‘They system is rigged’ becomes an excuse to regard only one’s own form of political participation as genuine. Everyone else is either complicit or a dupe.

In limited doses, that’s fine. But as it grows, that sort of thinking becomes dangerous. Because it regards one type of faith as the only correct form, and therefore poses a real threat to pluralistic democracy.

Progressivism and faith

All of which brings me to my deeper point. I’ve been speaking so far within the framework of ‘faith vs. realism.’ But, it should already be clear, this is flawed in its very formulation. Because the ‘realistic’ approach isn’t antagonistic to faith—and it does neither side of this debate any favors to treat it as if it were. The realistic approach isn’t about ‘truth over belief;’ it just reflects a different sort of faith.

And, in an important way, what I’m talking about here unifies these conversations. Those who believe in the possibility of the Sanders campaign often finding themselves at war with two theoretically distinct groups. The first is the numbers-crunchers, who make ‘value-neutral’ claims about who will win. The second is the centrist liberals, who like ‘what Bernie stands for’ but ultimately prefer to go with the mainstream, wonky, ‘progressive who gets things done.’

But what should now be clear is that both of those groups are singing off the same songsheet. They both ground their perspective on the campaign in a deep-seated faith in the progressive perfectibility of our systems.

Writ large: they believe in the narrative of progress. And they see progress emerging through the slow, but linear accumulation of knowledge—tweaking things here, adjusting things there, and eventually making real improvements. The underlying sense is that to fix a thing, you must first understand it. And, as a result, change very rarely comes in big sweeps. Instead, it arises via painstaking accretions, through the “strong and slow boring of hard boards.”

All of which is to say: these days ‘progressivism’ has become a bit of a floating signifier, and both Clinton and Sanders really want to assert a claim to that label for themselves. But what I’m describing here is one specific way in which Clinton really does fit into the historical narrative of progressivism in a way that Sanders (and especially his supporters) really don’t. Progressivism in its 19th century roots was very much based on faith in the perfectibility of systems through the application of human reason and ingenuity. It believed in capitalism, but wanted to harness it. It believed in regulation but had no interest in system change.

The theology of pluralism

And, most importantly for my purposes, it reflected a deep-lying faith that ‘what unites us is far greater than what divides us.’ Or, as (then Senatorial candidate) Obama once said: “There’s not a liberal America and a conservative America; there’s the United States of America. There’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.”

Put simply: this kind of faith is grounded in a fundamental belief that difference can be exceeded, that horizons can be fused (Horizontverschmelzung). But, and this is crucial, this is only possible if we see each other for what we really are. It’s not enough to know what’s right; you have to understand. Which means grasping why other think differently. It means accepting the validity of those with whom you disagree. It means taking them for what they are, not insisting that they must be something else.

And it means holding onto the possibility that politics (dirty, grimy, everyday politics) possesses an intrinsic value. More broadly, that the back and forth in which we attempt to convert others to our point of view, and genuinely accept that they might convert us, is the apotheosis of democracy.

Which is not to say that politics is pure, or uncorrupted. Of course it’s not. And of course it rarely matches up to this ideal. But in spite of those failures, there’s something inextinguishable at the heart of the process. A sort of fundamental dignity evoked by the principle of pluralistic politics—in which people disagree with one another about the appropriate policies, goals, ideologies, etc. but everyone agrees with the baseline premise that political systems.

Does this all sound fanciful and utopian? Well, sure. It is fanciful and utopian! Just as Sanders supporters believe in an ideal of America, in spite of evidence that suggests it’s miles away, those who believe in politics of this sort hold onto their own brand of faith. It motivates them to seek out marginal gains where possible. To embrace the value of making ten or a hundred lives better, in the hopes that thousands or millions will someday follow.

I don’t ask or require that you share this belief with me. But I do think it’s important that you respect it. Because if faith in Sanders and what he represents comes packaged with such deep cynicism that it can’t even acknowledge the possibility that politics itself might bring good into the world, I have a hard time seeing how it’s ever supposed to work.

And, by the same token, it’s incumbent on the ‘realists’ to get off their high horse, to recognize their own deep utopianism, and to regard the beliefs of those who see a different trajectory as noble rather than objects of mockery.

If we can’t even do that much, it strikes me that neither perspective really has much to offer the world. Because without even that basic level of shared understanding, I don’t see how democracy of any sort can ever succeed.