Howl – The Gaslight Anthem

Mae – The Gaslight Anthem

2012 is turning out to be a pretty good year for bands that sound like Bruce Springsteen. For one thing, Bruce himself came out with one of his best albums since the early 80s. Lucero’s got a solid record (to be reviewed at some future date here). And The Gaslight Anthem have a record that continues to legitimate their claim as the kings of the post-Bruce genre.

It’s called Handwritten, and you get the sense that this appeal to authenticity is not just an affective thing with them. In lyrics, style, attitude, and every other way imaginable, these guys want to communicate the importance of doing things the right way.

That means a lot of things. It means a commitment to the true spirit of rock and roll. It means believing that anthems of love and passion really do contain within them the possibility of becoming something more. That redemption is rare but real, and all the more precious because of its rarity. That the coolest kid around is the one who can dare to be earnest.

In this respect, this is the album where the Gaslight Anthem have become almost more Springsteen than the man himself.

By which I mean: this sounds like the album that Bruce Springsteen would write if he were a character in one of his own songs.

As I have written in the past, Bruce has always been a lot more skeptical than his critics have assumed. The Springsteen tropes exist not because they’re meant to reflect a real story of the world. No, they exist because they provide the background narrative of his imagined universe. They tell us what his characters want to believe about themselves. The guy who shows up at Mary’s door with the promise of redemption inhabits the same world as the Vietnam vet who lost his brother at Khe Sanh. And they both stand in as archetypes for the guy who is trying to write his novel and just can’t make it click.

Cars mean freedom, but they also represent wasted years spent on ephemera. The train is the universal metaphor—it takes us into the land beyond, brings us all together, forms the connective tissue of our greater psyche. And these vehicles scream to us of salvation and redemption. But the broader point, made clear only from the distance as the whole narrative blends together, is that redemption was never in the thing. Redemption is the thing, and it comes from our capacity to believe.

Look at Thunder Road. He sings “All the redemption I can offer, girl, is beneath this dirty hood,” and if you want to be ungenerous you would interpret that as a belief that the car is some simplistic metaphor for freedom. That the American Dream is found in some fuel-injected engine. But that’s not the point at all. No, it’s the act of offering that matters. The substance of the offer is what gives it a narrative hook. But if you treat the hook as the thing itself, you are doomed.

Of course, Springsteen drifts into that sort of cliché and self-parody at times. But at his best, there’s this additional level of depth. The characters may believe in the symbolism, but they are portrayed with a sympathy that lets us, the observers, see the larger magic at work.

The kid sits there with hand outstretched, and asks her to share his dream. But the dream is not the magic of the highway. It’s not the perfection of handwritten notes. It’s not the majesty of the river. The dream is the dreaming itself. The finding out, the testing, the endless faith in the possibility that there must be something more. And if we can’t find it here, then we just have to keep looking.

When we come to believe that the thing itself is our redemption, then we come out on the other side of Springsteen’s American Dream. On that side you see the sad lovers of Racing in the Street who can barely stand to look at each other anymore. Or the killer in Nebraska who can only believe in a ‘meanness in this world.’ Or the vet who has ‘nowhere to run, ain’t go nowhere to go.’

These are the anti-heroes, the ones who believed in something and saw it fall through. They are older, bereft of passion, leading lives of toil and pain. They’ve lost their belief. But it’s because the thing they believed in was the song instead of the singing.

And that’s the thing about this Gaslight Anthem album. Like I said, it is earnest from start to finish and wrought with a great deal of care. But as beautiful as it is, I can’t help but feel like it suffers a bit in comparison to the depth you hear in Springsteen. That is, this record is full of things to believe in, but it holds onto those things like talismans. And this can occasionally obscure WHY that belief is so powerful.

Don’t get me wrong; this is a great record. It’s just not quite as good as it needs itself to be. Because there is no narrative structure, these songs are experienced as little slivers of possibility. They are iconic, but lack the depth of possibility that places them in a larger pattern of meaning.

“Handwritten” gives us the songwriter, scratching out a song in the moonlight, transcribing the fullness of his own soul. It’s an ode to the way that music reaches across distance and possibility and connects us together. But you can’t help but wonder who this person is. What specifically drives him? The impulse to say that music is universal is powerful, but it trends too far into its own halo in the implication that the nature of this universality can be captured in the bared heart of the poet.

“Mulholland Drive” dances close to the edge. Phrased as a question, it asks the one who left what happened to all the promises. It threatens to come across like a vicious caricature, with the white knight who offered true love to rescue the girl who then repaid the debt by scorning him. If that’s what the hero is offering in terms of redemption, then I’ll happily pass. It’s the sort of song that has the potential to really reflect the grey areas where everyone is to blame and none are at fault. It just doesn’t quite make it.

The defining feature of the very best songs on the record is their capacity to get past this fascination with the thingness of an experience. For example, “Here Comes My Man” is a delicate portrayal of the ambivalence that comes from past loves. It succeeds because it portrays the experience rather than idea. And “Mae” provides the specificity that’s often missing elsewhere. You don’t just get the sense of longing – it’s conveyed in aching detail. And it’s here that the ode to the possibility of magic on the radio. Fallon sings “We work our fingers down to dust / while we wait for kingdom come / With the radio on” and you know precisely what it feels like.

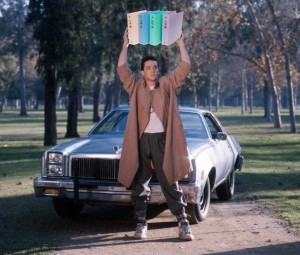

The highlight of the record, though, has to be “Howl.” This seems to be a deliberate attempt to return to Thunder Road. There’s a girl whose dress waves, a guy with a car offering to take her away. But it’s pitched toward the future, to a Mary who said ‘no’ to the first offer. She stuck around, went to school, and made a life for herself. And now our hero sends out a final missive: you know where you can find me, and all those plans I made might still have some life in them. It works because it’s audacious, it works because it feels REAL, and it works because Fallon absolutely sticks his lines. “Radio, oh radio / do you believe there’s still some magic left somewhere inside our souls?” The pain is tangible, and the hope even more so. On an album that’s full of insistence that the radio really might just save us, this is the shining moment where it feels absolutely and completely possible. So when he sings “I waited on your call and made my plans to share my name” there’s nothing you can do but hope along with him.

“Howl” lasts just two minutes, but in that time it conveys all the possibility of this band. If they could spin that magic out over the course of the whole record, this might be the best record of the decade. As it is, it has to settle for merely being very very good.