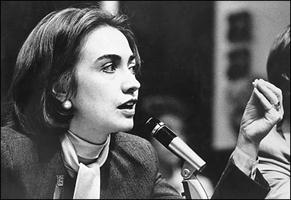

This weekend, Dara Lind at Vox wrote an excellent piece on the persistent left-wing critics of Hillary Clinton. Its hook is a question that is deceptively simple: “is there anything Hillary Clinton can do to redeem herself to you?”

The context for this question is a process of decaying political legitimacy – and the difficulty many people find in believing that ‘establishment’ politics has anything to offer. Such skepticism is nothing new, of course. American politics has long been defined by suspicion of institutions, lack of faith in elite representation, and paeans to the wisdom of the people. We inhabit a politics of dissent and protest, punctuated by periods of quietude. And given the broader context, it’s wholly unsurprising to observe a growing tumult of protest and critique.

Lind’s question, however, asks us to seriously consider the underlying political commitments of such critiques. If institutional legitimacy is weakening, what is the appropriate response? Is the goal to recuperate our institutions, or to hasten their destruction? To double down on de-legitimization, or to work toward their redemption?

The politics of getting to ‘yes’

Hillary Clinton clearly endorses the curative message. She is the candidate of the status quo, insofar as she represents faith that our politics can accommodate dissent by rectifying the injustices that spur this kind of doubt. And this is where Lind’s question becomes crucial. Clinton sees America as a cacophonous conversation of countless beliefs and creeds and races and identities, but a conversation in which everyone remains open to the goal of finding a way to get to ‘yes.’

Not an uncritical or irrevocable ‘yes.’ Not a ‘yes’ which silences dissent. The only requirement is a willingness to clearly articulate acceptable partial steps, and to bargain in good faith toward those results. This is what transforms delegitimization into critical collaboration. Which says ‘although we don’t agree on many things, we regard each other as shared participants in a political world.’ In effect, she is telling her critics that she will genuinely listen to their concerns. And she is asking them to do the same.

Indeed, if there is an essential motivating force behind the Clinton campaign (and more broadly, behind the modern Democratic Party writ large), it’s the belief that politics should be driven by the effort to include those who would like to be included. That motivation has built an inclusionary party, one grounded in tolerance and diversity, one housed in a big tent with a lot of ideological diversity.

This all helps to make sense of Clinton’s ongoing campaign to win over moderates and Republicans. Those efforts have engendered a lot of (understandable) anger from the left, who have no time for paeans to Reagan’s optimism, for patriotic chants, for Republican endorsements. And it has led many to express serious doubts about the sincerity of Clinton’s commitment to progressive politics, and her flexible political weathervane. If she is willing to speak the language of both sides, does she really believe anything herself?

Beyond ideology

These questions are not entirely unfair, but they risk becoming overdetermined, reducing all questions to their ideological coordinates on a straight line from left to right and thus stripping away the multidimensionality of politics. Missing from this account is a recognition that legitimacy creates a second valence of American politics, which does not simply map onto ideology but instead operates on a tangent to the right/left line.

Clinton’s appeals are grounded in the desire to work toward mutual understanding, and to seek viable terms of collaboration. Her appeals do come from a specific ideological coordinate, to be sure, but they are not wholly defined by that location. She values the process of getting people to ‘yes’ – and further values the system through which such collaboration is possible.

Here, I think her long-noted affiliations with the great Saul Alinsky are particularly notable. Alinsky argued forcefully for the necessity of radical action. And, more than that, he argued that those committed to the cause of justice must sometimes be blind to alternative logics. They must believe in their cause forcefully, at a level that exceeds the scope of reason. And yet, he insisted, such radical politics is not just compatible with compromise, compromise is its lifeblood:

If you start with nothing, demand 100 per cent, then compromise on 30 per cent, you’re 30 per cent ahead. A free and open society is an on-going conflict, interrupted periodically by compromises—which then become the start for the continuation of conflict, compromise, and on ad infinitum…A society devoid of compromise is totalitarian. If I had to define a free and open society in one word, the word would be ‘compromise.’

Clinton, of course, is no radical herself. And yet I believe she still regards the political terrain in the same essential terms. If she is no radical, she nevertheless seeks to sustain the function of political institutions capable of engaging with, and facilitating gains by, those who stand outside.

So, for those on the left who remain deeply skeptical of Clinton, this raises a crucial question: to engage in wholly ideological terms—seeing Clinton and the Democratic Party writ large as essentially untrustworthy—or to engage in the politics of collaboration? If they choose the former, they refuse her invitation to enter ‘the room where it happens,’ and thereby offer few incentives for resolution. Someone who cannot say ‘yes’ to any offer is an unwelcome participant in such conversations—not because their ideas are bad, but because they are working to undermine the very structure of decision-making.

The politics of radicalism and the politics of rejection

This is by no means an easy question. There are deep problems in our political order, inequalities that far exceed the limits of marginal tinkering, distrust that blooms all the brighter with each passing year of incremental change. Under those conditions, there is a real argument to be made against accommodation, and I take that argument tremendously seriously.

Nevertheless, I worry that these arguments risk obliterating the distinction between a politics of radicalism and a politics of rejection. Both seek to break the shackles of our imagination, refusing to regard the status quo as fixed, or the terms of engagement as intrinsically constrained. But they differ, in that the politics of rejection tends to dematerialize the experience of justice, seeing collaboration with violence as merely a step removed from its direct infliction, no less cruel in its underlying affect. Radical politics admits many shades of grey; rejectionist politics sees only heroes and villains (friends and enemies).

It’s important to really think through this difference. Not because one approach is ‘good’ and the other ‘bad’ in some objective sense. This is a difficult topic, and one where people of good faith and strong beliefs will find themselves in disagreement. And that is as it should be. A politics without dissent would not really be politics at all. So the goal isn’t to discourage dissent, but rather to find ways for it to be more powerfully and productively expressed. And that is something that requires serious self-reflection from all sides.

Conclusion: what are we talking about when we talk about politics?

My argument here speaks to the very heart of contemporary debates within liberalism. So in one sense, it is critically important. A failure to seriously consider the terms of our engagement risks fomenting further alienation and dispossession. At the same time, the stakes are also relatively low. Accepting the existence of differences here doesn’t require surrender or significant reconfiguration of ideological commitments—just a little bit more understanding and self-reflection.

For the ‘establishment,’ it is crucial to remain open to the legitimate concerns of protestors. Even if their commitments appear naïve or unrealistic, they are nevertheless genuinely felt and deserve engagement rather than derision. To regard protestors as illegitimate, and therefore worthy of dismissal, is to counteract the very logic under which institutional legitimacy itself is supposed to operate. The core premise of this mode of politics, after all, is its capacity to listen and take seriously the concerns of all, not just those who already agree.

Put simply, there is a powerful argument for the politics of collaboration, but such arguments are perpetually in danger of becoming hoist on their own petard. That some refuse to engage cannot become a justification for dismissiveness. The door must remain open, in the hope that these powerful ministers for justice might one day walk through. Or, as sometimes happens, to leave an escape route for those times when the drumbeat of justice beats so heavily that it shatters the foundations of normal politics (as, for example, happened in the case of slavery).

By the same token, it’s far too easy for those on the ‘protest’ side to stumble into a Janus-faced mode of critique: pitching critiques as collaborative, but persistently moving the goalposts about what meaningful accommodation really entails. This is dangerous because it tends to provoke further alienation on both sides—especially since this sort of double-dealing is very rarely intentional. That is: those who engage it almost never regard themselves as negotiating in bad faith. But in practice it ends this way, because the process was engaged from a premise of distrust where ideologically distant parties are seen as antagonists who must be tricked or bullied into accession. When such efforts fail (as they inevitably must), future engagement is unlikely. If concessions win no points and earn no good will, they are unlikely to be repeated.

This means that engagement, if it is to be of any use at all, requires serious consideration of underlying expectations and demands. It does not require backing down on ideological commitments, but does depend on the willingness to regard ideological contestation as taking place within a shared universe of (potential) understanding and engagement. It means, like Alinsky, seeing a 30% victory as a real victory, the only sort of victory usually available, and thus worth getting your hands dirty to achieve. And it means having faith that those with whom you disagree may nevertheless become agents for, rather than against, justice.

All resolutions will inevitably be unsatisfactory, diluted. It cannot satiate the demands of justice and will not quell dissent. But it does offer the potential for common cause. Not agreement, but productive conflict. And grounded in a shared world, if not always in shared values.