Graph from: The Plum Line

Graph from: The Plum Line

Relative Surplus Value – The Weakerthans

It’s a pretty common lefty-blog feature to point out that the American public is totally incoherent when it comes to governmental spending. And with good cause! People generally state preferences that wildly contradict with no apparent awareness of this fact.

The general premise is that everyone wants to cut wasteful spending and reduce deficits. But when faced with a variety of specific questions about what to cut, clear majorities favor retaining spending on virtually everything. And even on those few things that majorities think should be cut, there are still very silly elements. One example is the report discussed here, which points out that foreign aid is one of the only things people want to cut. However:

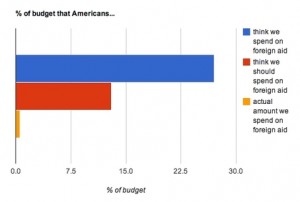

In a World Public Opinion poll conducted last November, respondents guessed, on average, that foreign aid spending represented 27% of the federal budget. To trim spending, the same respondents suggested that, on average, foreign should make up a slimmer 13% of the total budget, surely delivering massive savings.

The problem? Foreign aid is actually a minuscule 1% of the total budget. Even eliminating it altogether would do little to balance the budget or reduce the deficit.

Right.

That is all totally fair, but I want to make two points that might help to at least reduce the confusion and maybe will redeem the American people at least a little bit.

First, I think it’s important to remember that when people complain about ‘deficits’ it very rarely means they actually care that much about deficits. What they don’t like is a bad economy. The thing is: the economy is unbelievably complicated. I study politics for a living and read a lot about the economy and still find myself completely lost when trying to go beyond the fairly basic stuff. For people who devote significantly less attention, it’s not at all surprising that they speak in a sort of shorthand. The one thing that was pretty commonly agreed upon in the 70s and 80s was that federal spending commitments had gotten out of control and contributed to the serious inflation problems that hit the country.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that. But there’s enough truth there to pass the smell test. And it works at a gut level, too. When times are tough for individuals, the responsible thing to do is cut back on your spending. It’s just common sense that governments ought to be doing the same. And the money they’re using is taxpayer money! So it’s doubly offensive for them to be profligate while common people suffer!

What’s missing from that morality tale, of course, is that governments aren’t people. They don’t spend money to increase their own utility.* The money they’re spending is (at least in principle) going toward improving the social conditions of the whole country. And the task of a government in tough economic times is to serve as a counterweight to the individually rational decisions to reduce spending (and thus reduce liquidity). But that’s a complicated argument. And as long as things are bad people are unlikely to want to listen to it.

You’ll find that as economic conditions improve people’s worries about the deficit fade tremendously. That doesn’t really make sense unless you accept that, for many people, ‘I’m worried about deficits’ is a stand in for ‘fix the damn economy!’ There are genuine deficit hawks, of course, but they are nothing close to a majority. We can keep feigning astonishment at this phenomenon if we want. But it’s almost as silly as the people who claim to care so much about spending while refusing to cut any spending.

The second point pertains to the foreign aid example. It is, of course, an important point that people monumentally overestimate the amount of money we have going to foreign aid. And it’s worth pointing that out. But I often see people taking this example as evidence that the public would actually support more spending on foreign aid, or at least doesn’t ‘really’ want to cut foreign aid.

I think that misses the point. People are terrible TERRIBLE judges of absolute numbers. We are much better at relational assessments. That means that when people said they thought foreign aid should be 13 percent instead of 27 percent they didn’t really mean it should be 13 percent. They meant that we should cut foreign aid in half.

I bet that if you had said ‘let’s say foreign aid is 20 percent of the budget, how much ought it be?’ they would have said 10 percent. Or if you had said 10 percent they’d counter with 5 percent.

The point is not that we should listen to people and cut foreign aid spending in half. It’s just that we should take all these ‘public opinion’ surveys with about 27 grains of salt. They DO tell us things, but it’s often not the things that show up on the surface.

* Yes, yes, institutionalism tells us that governments do in fact take on personalities and interests that are detached from their representational origins. And bureaucracies, in particular, as susceptible to path dependency and capture by particular interests that then work hard to sustain spending for wholly internal purposes. This is all true, but is still a relatively minor subset of what we’re talking about.