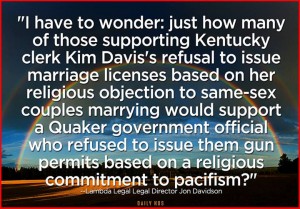

I want to talk a little bit about Kim Davis, the Kentucky clerk who has just been jailed for refusing to issue marriage licenses to same sex couples. In particular, I want to talk about the way that a lot of liberals have attacked her position. Here’s a good example, from Daily Kos:

I have very little patience for Argument By Hypocrisy in most circumstances, and this is no different. My question is: what happens if we reverse the terms?

That is: just how many of those mocking Kim Davis’s refusal to issue marriage licenses based on her religious objections would similarly mock Martin Luther King Jr. calling for public officials to refuse to enforce Jim Crow laws based on his religious objections? And how many would mock Henry David Thoreau’s refusal to pay taxes to a state that permits the continuation of slavery? And how many would mock a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War?

My point is emphatically not to say that Davis is right in her position, but instead to resist the form through which her principles have been attacked. Because these are principles–terrible principles, yes, but principles nonetheless–and we do a disservice to ourselves if we reduce this to simply an assault on the very notion of principled resistance.

In short, I am troubled by the way that the very idea of morally-grounded civil disobedience has come under attack in these comments. Because that isn’t the real issue at all. The problem is much simpler: it’s the content of her moral beliefs, rather than the principle that moral beliefs can, under some circumstances, provide a counterweight to the pure rule of law.

Let’s go back to our Thoreau, to see what he says about the relationship between liberal democracy and religious objectors:

I do not hesitate to say, that those who call themselves abolitionists should at once effectively withdraw their support, both in person and “property, from the government of Massachusetts, and not wait until they constitute a majority of one, before they suffer the right to prevail through them. I think that it is enough that they have God on their side, without waiting for the other one. Moreover, any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a majority of one already.

How about Martin Luther King, Jr.:

You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, it is rather strange and paradoxical to find us consciously breaking laws. One may well ask, “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer is found in the fact that there are two types of laws: there are just laws, and there are unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “An unjust law is no law at all.”

Again, I do not think that Davis should be allowed to deny licenses. I don’t think she should be permitted to continue in her job if she won’t perform the duties that it requires.

But I do think she has the capacity, as a moral being, to raise these objections without categorical dismissal. Just as we have the capacity, also as moral beings, to disagree with her interpretation of the ‘higher’ law. Which, again, is precisely the terms on which King made his own arguments against segregation:

How does one determine when a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law, or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas, an unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. … Paul Tillich has said that sin is separation. Isn’t segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, an expression of his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness? So I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court because it is morally right, and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances because they are morally wrong.

I agree with your position that we may all take principled stands, but Thoreau and King are arguing against positions of power whereas Kim Davis is the power. Neither Thoreau nor King argue to disenfranchise anyone, oppress anyone, or harm anyone. They argue for equality and human dignity. Davis, on the other hand, does disenfranchise, oppress and harm. She inflicts her principles on others for her own benefit. In making a point to those who support Davis, Daily Kos is right to point out the hypocrisy of the situation: if one wants to be in the right, one should seek to be in the right not only when it is politically useful, but always. Kim David may stand up for her hateful principles–sure, she’s an American–, but she should do so (as you point out) as a private citizen, not as a public official.