In poll after poll, both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders come out strongly ahead of Donald Trump. But Sanders is almost always further ahead. And while this is interesting, it tells us essentially nothing about how Sanders would actually fare in a general election.

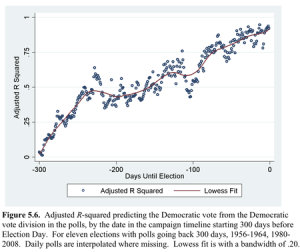

I’ll start by noting that there’s a decent amount of research on the question of general election polling, which mostly tells us that polls this far out are at best weakly indicative of future results. The reality is that, outside of highly mobilized partisans, most people simply haven’t thought that much about the campaign.

Generally, the historical record tells us that polls begin to stabilize a bit around 200 days out (right about where we are now). That’s likely because this is the time where the primaries are finished, and people start to focus on the upcoming race. That’s important not just because it intensifies attention and focus. The next big inflection point is late summer, after the conventions. Once you get that far, polls tend to get become quite trustworthy.

It’s plausible that 2016 will end up being a lot more stable, since the candidates are already exceptionally well known and people have likely reached settled opinions about both of them. But still, the general rule remains true: the vast majority of Americans simply haven’t put any meaningful time into deciding who they want to vote for.

None of this is to say that these polls contain zero information. They do tell us things. It’s just that the things they tell us have to be understood in context. And that context tells us that there are two big reasons to think that Sanders’ numbers are soft.

First, he hasn’t been attacked. Sure, Clinton has been running against him, and I’m sure many Sanders supporters have felt under attack. But her campaign has been notable for being almost fanatically defensive. Her technique has been to agree with his premises, hit back a little on guns and on lack of attention to detail, and then talk about her strengths. That looks nothing like the barrage of attacks a general election would bring on.

To be clear, Sanders has won a lot of support for good reasons. He is a smart guy, passionate, and clearly very genuine. People appreciate all those things, and rightly so. He’s also pushing for a lot of things that people care a lot about. Improving the condition of the poor and middle class, limiting the influence of money and special interests, etc. These things are also very popular.

But let’s not kid ourselves. The abstract popularity of an idea is very different from popularity in the trenches. You don’t have to look very hard to find evidence of exceptionally popular things going up in flames as soon as they get scrutinized. 90% of Americans wanted ‘background checks,’ but once an actual proposal was on the table (and was being attacked), that support quickly dissipated. Many people may like your principle, but will turn quickly away as soon as the rubber meets the road. And even specific to Sanders supporters, polling indicates that lots of people would be far less willing to support his agenda once they find out the details.

It’s certainly possible (albeit improbable) that Sanders would continue to poll as well once he’s been subjected to a fusillade of Republican attacks. But those attacks haven’t happened yet (and never will), so current polling simply can’t tell us how things would look in that hypothetical world.

What’s more, the problem actually runs deeper. Even if the Sanders agenda and persona could withstand the content of these attacks, it would still run into the second fundamental problem: politicians grow more unpopular the closer they get to becoming president.

Right now, one of Sanders’ key polling advantages is the fact that he’s never been especially close to winning the nomination. This may sound paradoxical, but it’s a very real effect. The American public is significantly biased against those who are perceived as internal to the partisan political bickerfest. And, correspondingly, it valorizes those who appear tangential to those fights, who represent our ‘better’ politics. Sanders is currently drafting on that effect.

But there is one surefire way to lose this mantle: become the nominee. This is because the lauding of ‘apolitical’ figures is only tangentially about those figures as such. It’s far more to do with drawing comparisons against those who are currently trained in your sights. The result is that insurgent politicians get all the credit and very little of the flak. They stand for an alternative to the stuff people hate, rather than being a representative of it. But once the politician is in the midst of the political slog, every theoretical negative (which would be easily brushed aside before) is accentuated.

Want evidence? Check out Hillary Clinton’s approval ratings from 2010-2012.

+30!

This is a period when she was lauded for being above the fray, competent, capable. And above all: for not being Barack Obama. But once she began running for president again, her support plummeted. Not because of any change in her; because of a change in her circumstance.

More evidence: George W. Bush. His approval ratings were in the 70s in the fall of 1999. A year later, in the midst of a general election campaign, they had fallen 20 points. George HW Bush, during a bruising fight to retain the presidency, saw approval ratings fell into the 30s in October of 1992. Two months later, they had jumped into the high 60s. Mitt Romney was +13 in February of 2012, unfavorable on election day.

John McCain is maybe the closest analog to Sanders. He managed to remain quite popular, even with the partisan filter. Still, his support dropped from +20 in the early summer of 2008 to +6 by the election. For a lot of people, he stopped being ‘John McCain, war hero and great guy’ and became ‘John McCain, politician.’

The point of all this is not that Sanders is terrible, or that he’d have been a disaster, or anything like that. Facing Trump, I think he’d have been a perfectly solid candidate. While the effects I’m describing are real, they aren’t 100% dispositive. The underlying strengths of Sanders wouldn’t disappear. He would likely have much higher personal favorability ratings than (for example) Hillary Clinton currently has. And while his agenda would suffer quite a few sustained attacks, having that debate might well be worth it.

But at the end of the day, whether Sanders would be a strong general election candidate is almost exclusively a question for punditry, not analytics. The polls just do not produce useful information about this question, no matter how much we might want them to. They simply can’t tell us how people would have thought about Sanders as a general election candidate, because they are snapshots from a world where he isn’t one.