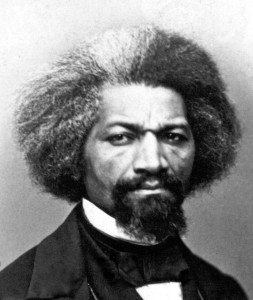

It’s never a bad idea to spend some time with Frederick Douglass, and I’m taking the opportunity today to remind myself of his brilliance by re-reading his speech on The Meaning of July Fourth to the Negro.

It’s a blistering speech, full of righteous anger and scorn for those who would seek to dodge or dissemble. But it’s also a speech full of wonder and hope. It affirms the text of the constitution against those who seek to justify the injustices they render. It affirms the message and not the men. It’s important not to lose sight of both of these elements. And to recognize the bracing form in which they are blended together.

Douglass begins with a traditional hailing of the Founding Fathers, of the great dream of the nation, of the wonder that such a thing could have been achieved. But then, he turns back onto the audience, breaks the fourth wall, and asks them directly:

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

…

But such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common.-The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

One can imagine the reactions of his Rochester audience on that day. To fancy yourself enlightened and fair–asking this great man to come and speak–only to have these words hurled back in your face. To find yourself an object of scorn and disgust, grouped together with the slave owners and overseers of the south.

And Douglass certainly anticipates that response. He continues:

But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, “It is just in this circumstance that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on the public mind. Would you argue more, and denounce less; would you persuade more, and rebuke less; your cause would be much more likely to succeed.”

For Douglass, there is nothing more infuriating than such equivocations. Particularly on a day dedicated to the celebration of the very phrase: “we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.”

The hypocrisy is stunning, the rage it induces overwhelming, the pain indescribable. All of the kind words he first issued now taste like ash. A reminder of our sins, of our unwillingness to act upon those simple moral truths.

And yet, after enumerating these sins in excruciating detail, Douglass winds his way backward again. At the conclusion to the speech, he finds himself once again enunciating the promise of America. And once again glorifying those very documents he has now spent so long excoriating.

Look to the Constitution, he says, and you’ll find no defense of slavery. Look to the Declaration, and you’ll find no denial of humanity. In these emblems of our nation, the slave is citizen as much as any other.

And here, amidst all the rubble, he identifies an ember of hope: “Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.”

With this, he holds out a branch to his audience. As if a drowning man were to hold out a branch to those safe and secure on dry land. But he is not asking them to bring him up to land, as they might have imagined when he began the speech. Instead, he is calling on them to grab hold of the branch and be pulled down together. Enter the darkest and stormiest waters, acknowledge the incalculable suffering all around us, bear that pain on your own backs, and feel the urgency of its end.

And with that, he concludes, in terms that felt eerily resonant for us and our political moment today:

“No nation can now shut itself up from the surrounding world and trot round in the same old path of its fathers without interference. The time was when such could be done. Long established customs of hurtful character could formerly fence themselves in, and do their evil work with social impunity. Knowledge was then confined and enjoyed by the privileged few, and the multitude walked on in mental darkness. But a change has now come over the affairs of mankind. Walled cities and empires have become unfashionable…The far off and almost fabulous Pacific rolls in grandeur at our feet. The Celestial Empire, the mystery of ages, is being solved. The fiat of the Almighty, “Let there be Light,” has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light.”